Creating Participatory Research: Further information on Learning Tasks

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 1

Learning Task 1 – The limitations of traditional research

In completing this learning task, you may have considered a range of limitations with the traditional research process, framed by the questions that were posed. For example, all researchers hold views about the social world that inform their practice. We all have biases and hold values and beliefs (personal and political) which can and do inform the topics that we are interested in, and the ways in which we approach data collection. More practically the tools used in any project may be flawed, and there are always issues with time, scope and resources which serve to limit research projects.

In terms of the relationship between the researcher and those providing data, this usually varies according to each research project, the methods and the questions guiding the process. If the research is quantitative for example, involving a randomised control trial, then the subjects will participate only as per the instructions of the researchers. Qualitative research usually offers participants the opportunity to contribute in terms of being interviewed or observed. Researchers using traditional approaches hold the power, and it is them who control the process which privileges their knowledge.

Traditional research can provide some insight into communities, their values and relationships. Anthropological research approaches involving ethnography offer such insights into specific communities but researchers generally remain external social actors even when they live and work alongside communities. This position means that they produce research findings that are likely to be different to those produced by internal community members. Power and position influence research in a myriad of ways.

Learning Task 2 – What is participation?

As noted in the first question of this learning task, participation may mean different things to people, and that there can be degrees and scales of participation within research projects. The word is frequently used in the literature in relation to research but there are clear differences between people participating in research who give an interview or complete a test, and those who aren’t experts but actually gather data or design research questions. Each study has to be judged on its own merits. The ladders described in the literature (Arnstein 1969 and Hart 1992) are useful tools for assessing research studies against.

Arnstein’s ladder can be seen as an image, with accompanying discussion here.

Hart’s ladder for youth participation can be accessed here.

Many studies that say they are participatory are not, they use the word but often look more like consultation and are tokenistic in the extent to which the process is committed to participation. Researchers may well have ‘good’ intentions about working in participatory ways but the realities of this are very challenging. Full participation in the research process for us, looks like community members being involved in all aspects (or those that they choose), from the beginning to the end. You can when working in practice use simple questions to ensure that people are participating fully, by asking if they feel listened to, and exploring if they feel that they have contributed to and been involved in the decision-making processes taking place at any given time.

Learning Task 3 – Inclusive research practice

You will need to consider the ways in which you work, and if these are accessible for the population that you wish to include? For example, many organisations use email as the main way to communicate. However, not everyone has internet access, some people are unable to read email content (for example if they are visually impaired), and some simply prefer a more ‘human’ approach such as speaking. Are venues accessible if you plan to meet people in them? Are you approachable and able to adapt to the needs of those that you are working with? How can you manage risk to yourself, and to those giving their time to you for example, if you need to visit people in their homes, or you are expecting community researchers themselves to do home visits?

How too might you support their involvement for example, are you able to pay travel expenses? Are you able to reward people in some way for contributing their time? This should not include financial payment, but could be in the form of training, certification and the provision of refreshments.

You will also need to work sensitively around the topic areas that are being explored. Here you will need to think about what you take for granted as an educated individual and how this relates to the context in which you are working. For example, it may not be possible to conduct research in some areas about homosexuality and/or HIV without negative consequences for the researchers and your participants.

There are many more aspects to consider here, those listed above are just a brief note (a starting point).

Learning Task 4 – Universities and participatory research

There are many top tips available in the literature, and on the internet. These are of course useful but the reality of doing participatory research remains a challenge – did you note this as one of the key points? Universities are structured institutions governed by procedures and policies that can limit their scope to undertake participatory approaches. All research takes time and some projects are afforded less time due to funder requirements, the life-time of community interventions, as well as competing priorities. Allowing time is noted as a top tip within the toolkits. Furthermore, researcher identities may be challenged within such approaches, with those in charge of projects having less power and control than they may expect or even be used to, which is not a comfortable space to inhabit. Despite the challenges, many researchers within universities do commit to using such approaches, as do students in some instances. This blog is a useful discussion as the author reflects on students doing participatory research.

Chapter 2

Learning Task 1 - Co-production and participatory research – different principles?

In completing this learning task, you may have considered the many similarities between the principles of participatory research and co-production, as there are clear overlaps between both of these approaches. For example, a principle that they both share is that professional researchers will work with non-professionals, and both approaches involve joint working.

Were you able to see any differences between the approaches? It may not be easy/clear to see any differences because there are many labels that are used within the literature to describe the variety of approaches used within participatory research. So is co-production just an extension of this approach, or a different label (along with the many others described in the book – see chapter 1, specifically table 1.2)? There is some debate about this in the literature, and certainly both participatory research and co-production in research are umbrella terms that encompass varying approaches and methods.

There is no clear answer to this learning task, because as chapter 2 states, these approaches (participatory research and co-production) “sit alongside each other…[and] they share some underpinning philosophies.” (Locock & Boaz 2019: 409). However, other commentators see them as being different, Kagan (2013) argues that co-production is more than participatory research because participation can be at one or many stages of the research process, and therefore can be seen as existing on a continuum. In contrast, co-production is underpinned by sense making achieved through joint reflection. Having completed the learning task, whose viewpoint do you agree with?

Learning Task 2 - Exploring questions and challenges when co-producing evaluation

Were you able to take time to consider the questions posed by Hickey et al (2018) and answer them clearly and easily? A criticism that co-production and participatory approaches share is that whilst they are underpinned by a principle of power sharing, that the reality of their application is more difficult, and that power-sharing can therefore be tokenistic when researchers have deadlines, are expected to produce findings in certain formats (reports and high-impact papers) and have to adhere to institutional protocols that may hinder working with communities. Furthermore, rigid ethical approval systems can limit the flexibility that is required to co-produce (see question 2 about current structures supporting and enabling co-production, and table 2.3 – the first example – which discusses the mismatch between university ethics and co-production.

In attempting to judge and evaluate co-production, chapter 2 later notes some of the challenges with this. For example, there is little formal evidence to support its use and much of the existing evidence-base is limited as it tends to be in the form of case studies. Evaluating co-production also requires a focus on processes rather than pre-determined outcomes. Chapter 2 does go on to offer some example guidelines that might be of use, and these are certainly useful as basic benchmarks/starting points for all of those engaged with co-producing research.

Questions about co-produced research being taken seriously and needing more credibility are also well discussed in the wider literature, and therefore discussed in chapter 2. The increasing attention being given to such approaches by funding agencies is promising, but there are many challenges that still need to be addressed.

Learning Task 3 –Exploring experiences of co-production

Which of the reflections did you choose to read through and why? Were you convinced by those that offered positive messages about co-production? Did you also notice that there were discussions of some of the issues and challenges that arise when using such approaches? One of the key messages for us when we completed the activity was that people are often keen to try these approaches and committed to using them which can result in very positive outcomes (such as increased confidence for service users) but that there will always be challenges and debates. Did you reach a similar conclusion, or did you have an entirely different view? For example, did you conclude that there is no point to co-producing research after you had read some of the blog posts? Reflect upon why that might be the case – is this about your own values, experiences and standpoint as much as is about what you read?

Learning Task 4 - Exploring resources that support co-production

Which of the resources did you choose to look at? Did you find a useful model that would help you to work in a co-productive manner? We explored the Connected Communities web-page and read reports related to methodologies – not surprising given the focus of this book, and our interest professionally. Looking at these resources helps us to think about the types of methods that we might use in our own work, as we all learn from examples. Chapter 2 offers some useful ‘tips’ and frameworks and some links to further resources – so for anyone wishing to co-produce, there is a now a plethora of material that offers practical insights into these approaches.

Chapter 3

Learning Task 1 – Participation in formulating research questions

Participatory research works best when the research is aiming to accomplish something that is of value to the participants. You might find that answering your own research questions provides inherent value to the lay participants by providing evidence about something that they are doing, which can help them to apply for further funding to keep doing it (many interventions run by voluntary or community sector organisations are only funded by short term grants for example). On the other hand, the goals of the researcher and community members may be different, and you might consider including additional research questions that will meet the participants’ goals. For example, in a current project about community empowerment, the researchers and funders were interested in barriers and facilitators to people taking an active part in the community projects, but the lay participants were interested in researching digital exclusion in their communities, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research questions are now about digital exclusion!

Hopkins and colleagues have published a useful paper reflecting on the process of co-creating guidance, with young people, for involving young people in social research (Hopkins et al., 2017). It is clear from this that the congruence of the research with the values of young people (in this case, social justice and fairness) is a critical factor in determining whether the young people are willing to participate.

Learning Task 2 – Methodology: qualitative or quantitative?

Much participatory research is qualitative, but surveys are a popular choice if the research question lends itself to a quantitative design, and these can be administered face to face, using paper (the well-known clipboard approach) or tablets, over the telephone or online. In the book chapter, an example is given of an epidemiological study on air pollution that took a participatory approach, so do think creatively if you have a quantitative research question, about whether it can also be participatory.

Lay participants should have the opportunity to receive training in research methods, if participatory research principles are being followed. Training materials should be short, simple, engaging, easy to follow and remember, and ideally take into account different learning preferences (e.g. visual, audio, or written). A good format for delivering training is in a series of workshops, where participants can ask questions and support one another. On the other hand, attending a series of training workshops is a big commitment in terms of time, and not all participants will be willing or able to do this. Training has been identified as both a facilitator and a barrier to engagement in studies of community engagement (e.g. Harden et al., 2015; Bagnall et al. 2016). One pathway to overcoming this is to build training into the initial discussions between academic and lay researchers, with the aim of reaching agreement about how much and in what format the training should be delivered.

Differences of opinion can be resolved by means of discussion, voting or other means. Be careful here, as power imbalances can re-emerge! The means of resolving disagreements should be decided in the initial discussions and agreement between academic and lay researchers.

Learning Task 3 – Participatory approaches and mixed method design

The examples in table 3.2 refer to different ways of combining qualitative and quantitative research to explore the issue of workplace stress in healthcare professionals. Any of these could be made more participatory by involving healthcare professionals in their design. You could:

- include healthcare professionals as co-investigators,

- take their lead on research questions of importance to them, and on the extent of their involvement, including time commitment.

- Co-design data collection tools such as interview schedules or questionnaires.

- Provide training workshops in research methods, for analysis.

Barriers to participation might include:

- Time commitment

- Knowledge of research methods

- Finances

- Childcare issues

- Health issues

- Accessibility, safety and familiarity of meeting places

- Transport

- Language

- Cultural or religious barriers

Can you think of any more? The easiest way to get the full picture in any community is to ask people!

In your team you will need people with research skills, teaching and training skills, soft ‘people’ skills for community engagement, dealing with difficult people and conflict resolution, organisational skills, and academic researchers may also need to train one another in the basics of their different disciplines and favoured methodologies.

Learning Task 4 – Challenges of participatory research design

The open access journal “Research for All” is a good place to start when looking for papers about the practicalities of conducting participatory research. A paper by Southby (2017) outlines a number of challenges involved for research students carrying out participatory research, based on his own experience of doing participatory research with people with learning disabilities for his PhD. These include:

- Adhering to the standard and procedures of an individualistic academy

- Fear of failure

- Sharing control

- Inexperience

- Competing priorities

- Time and effort

Chapter 4

Learning Task 1 – Exploring ethical codes of conduct

In completing this learning task, you should have reflected upon the use of standard ethical codes of practice and their applicability to participatory approaches. Most ethical codes are based upon traditional research, and so are not always clearly applicable to more participatory research designs. This issue and the wider limitations of ethical review boards in relation to participatory research are discussed in depth throughout chapter 4. For example, a review board has standard forms and procedures which are based upon a professional researcher being in charge of the research project rather than a community partnership. Standard ethical review is also built upon the assumption that the research design is clear at the start of the project, when in participatory research the study design evolves and is subject to change. Many researchers who work in more participatory ways have therefore developed additional ethical principles to be considered in relation to participatory research, as discussed within the chapter.

Furthermore, participation within the development or review of ethical codes of conduct from lay researchers is not a standard practice, despite some of the benefits that this might bring. Most codes of conduct are therefore developed by professional researchers for others like themselves. Standardising ethical codes, and principles has been useful for many institutions such as health services and universities, however this is recognised as not being helpful in all instances as some research approaches (such as participatory research), do not neatly fit into these standards.

Learning Task 2 – Ethics in participatory approaches

When you were thinking about standard research ethics principles, were you able to consider how they should be applied to participatory research projects? It is useful here to start with the standard ethical principles, and to then develop them further. For example, Kawulich and Ogletree (2012) discuss the need to go beyond doing no harm as a principle and to work within community relationships when doing participatory research. Participatory research needs to be approved of by community members as well as any traditional institutions such as universities, which is again taking the need for approval a step further to ensure that community members as well as researchers and official institutions are satisfied with the proposed research study.

In addition, ethical principles need to be considered in relation to each specific project and the context in which it is taking place. Banks et al (2013) talk about ‘everyday ethics’ as an approach that is needed within each participatory study. This is in recognition of the importance of context. Ethical principles need to be applied in practice. Theoretical guides such as principles hold different meanings to research participants and may not be as important to them as they are to official institutions. For example, one ethical principle is anonymity, which is seen as a way to protect participants. However, in some studies participants want to be identified as a mechanism to ensure that their voice is heard.

Learning Task 3 – Research values, positionality and ethics

In completing this learning task, did you consider your own personal characteristics and how these might influence your own research practice, in particular your attitude to ethics? You may not feel comfortable sharing your own personal characteristics with others, so here are some general points to help you to think about this in more depth:

- Were you born in the global north or south? If you were born in the global north then issues such as literacy, equality of access (education) and inequalities are likely to be less significant in your life when compared to someone from the global south.

- Your status and social characteristics can be an issue in the research process – you may not consider yourself to be privileged but how do you speak, what words do you use, how literate are you and how are these markers different to the people that you are doing research with?

- How are your own experiences likely to shape your attitudes to power – have you considered the power that runs through the research process? For example, do you speak for your research participants? If so there are issues of representation here, and power that need to be recognised.

- What is your expertise, and how does your ethics relate to this – see Helen Kara’s blog about ‘The Ethics of Expertise’ for more on this.

Learning Task 4 – Exploring the ethical implications of non-traditional methods

When you were completing this learning task, what were the non-traditional methods that you listed? Each method needs ethical consideration within its own right, as there are different challenges with data collection tools from an ethical point of view. As chapter 4 mentions there are ethical guides available related to visual methods (see) and guidance for researchers using the internet to gather data (see), useful as starting points.

- Identify the method/s that you are planning to use.

- Search for ethical guidelines associated with your specific method/s – there are many different examples available online. If you are unable to find a guide, then revisit traditional ethical guidelines and consider how you will need to adapt and expand upon these in relation to your own project.

- It is also worth searching more generally to find out how other people have been using different methods, and what lessons they describe as being important. These examples are often useful as a starting point in helping you to think about your own research approach and practice.

- You can also note the decisions that you make in your own approach and reflect upon these throughout the study as a form of ethical reflexivity.

Chapter 5

Learning Task 1 – Participation in designing questionnaires

Most questionnaires that you will find by searching academic databases will have been validated, but often only in a very specific population. Some questionnaires have been translated from other languages, and some are so old that the questions asked may now not be appropriate or perhaps even offensive! So it is very important to pilot any questionnaire that you are thinking of using to gather data from a particular group with members of the same group. Often, these will be the ‘gatekeepers’ or community leaders that you are relying on to put you in touch with a wider group of community members. There are some obvious issues to look out for though, before you even approach the community leader with a questionnaire to look at. Here are some of the issues you should be thinking about:

- Language: does the question make sense? Could it be misinterpreted? Could it upset or offend people? Is it too complicated? (remember a reading age of 9 should be assumed) Do you need an easy read version (ideally these should be co-produced with users)? Does it need to be translated into other languages?

- Responses: is it clear how people should answer the question (e.g. ticking a box)? Are the response categories mutually exclusive with no overlap between them? Is there an alternative way to respond for people with literacy issues?

- Length: Is it too long? Be guided by your participants. There is no use having a brilliant questionnaire if nobody fills it in because it is too long.

- Layout: Is there enough space between the questions? Is it pleasant to look at? Do you need to use a coloured background or larger font size for ease of reading?

- Format: paper or online? Online surveys tend to get a better response rate, but risk excluding people who don’t have digital literacy and/ or access to digital devices. What about people who are visually impaired – do you need to have an option to fill it in over the telephone?

Learning Task 2 – Participation in designing interview schedules

As for questionnaires, interview schedules should also be piloted with the population group that you are planning to collect data from, and very similar issues arise – the language should be accessible and easily understood, the interviews should not be too long, the questions should not be distressing, and some people or groups of people may need assistance, such as translation, or to be accompanied during the interviews.

Thinking about the population groups you are working with, how did you or will you recruit them? Which organisations, groups or individuals will you need to approach to gain access to the community members? Think about how you will ‘sell’ your research – whether in a letter, a leaflet, a video, a presentation or just a chat – and seek guidance from the ‘gatekeeper’ at an early stage about the best way to do this with that particular population. How will you handle disagreements or dissent in the group (this can happen even when piloting data collection instruments)? Do you need some training in how to handle conflicts or ‘difficult’ people? It’s worth asking the gatekeeper whether there are likely to be any disagreements within the group and where these might arise from – they will probably be happy to advise you on what to watch out for!

Learning Task 3 – Thinking about creative methods

There is a wide range of creative methods, and this is growing all the time. When thinking about which to use, consider your own preferences and talents as well as those of the groups you are working with. The best method is one that you all enjoy! It also has to be feasible, and you may need to draw on professional facilitators (such as artists, photographers or drama therapists) to equip you all with the necessary skills. This could be costly, so needs to be budgeted for. Sometimes creative methods can have a powerful effect on the research participants, and they (and you) may become emotional. Think about how you would handle this. Do you have the skills and experience needed? Will a trusted gatekeeper be available for participants to talk to if needed?

Learning Task 4 – Challenges of participatory data collection

It is worth looking at the Research for All journal for this learning task, as there are several studies that discuss the challenges of participatory research, including data collection.

Chapter 6

Learning Task 1 – Considering the applicability of participatory analysis

The extent to which each project can be participatory across all areas of the research process is likely to vary considerably depending upon a range of factors. If community members are interested in working on data collection, then some may also wish to continue and work on the analysis. If community members have enjoyed working as part of a team alongside professionally trained researchers, then a group approach to analysis could be a workable option in which to support a more participatory model/approach to analysis. Questions remain about what involvement in analysis is and should be given that many challenges are identified in the literature specifically in relation to analysis processes. Some lay researchers may have skills that are suited to analysis, as well as the time available to contribute. Others may need much more training and support.

Discussions in the literature suggest that involving non-academics in the processes associated with research analysis can produce and many positives have been noted, including different views of the findings and analysis that lead into more usable results for communities.

Positive outcomes for community researchers involved in the analysis are documented in the literature for example in relation to skills development, but more negative experiences are less frequently written about. In applying participatory principles to analysis, which is a challenging area of work for many professionally trained researchers, community members may not always have an enjoyable experience or achieve positive outcomes. Power and position in relation to the processes of analysis are likely to influence experiences in a myriad of complex ways.

Learning Task 2 – Analysis in practice

It is helpful to consider the possible stages and/or areas in which community members can and want to be involved in, should they wish to analyse data. For example, community members as part of their involvement in data collection may already have some ideas about key themes, if for example they have conducted a number of qualitative interviews or focus group discussions. That does not necessarily mean that they will want to work with lengthy transcripts and specialist software.

Community members are likely to bring a range of different skills to analysis processes, so in one project that we worked on, a former academic volunteered to analyse lots of detailed qualitative case study data, as she was skilled in this area and enjoyed the work. So in each participatory project, you will need to consider the skills of those you are working with as well as the training that you can/need to provide to support community involvement in analysis processes. Facilitating workshops to support conversations about data, what it means and how it can/should be presented is one way that participatory analysis can be done in a group format. You will need to consider developing strategies to support and encourage, as well as training those who attend, but not all data can or should be analysed in a group context. If your participatory project involves quantitative methods, then you may need to do some analysis before holding a group session, and then use the time in group to support discussion and reflection upon the data.

Finally, you need to build in feedback mechanisms to ensure that community members/lay researchers are made aware of the progress of the analysis as well as the importance of their contributions and their role in developing findings, and products for dissemination.

Learning Task 3 – Challenges associated with participatory analysis

Having completed this learning task you will no doubt have been able to find material that points out several barriers, difficulties and challenges in relation to involving community members in analysis. The learning task encourages you to consider your own skills, and the ways inn which you work as a starting point for reflection. Our skills, abilities and emotions are likely to be areas in which we face challenges in relation to supporting and including community members within participatory analysis – challenges do not arise solely from lay researchers. Power dynamics, pressures associated with funding, institutional contexts and the circumstances of our own lives are all worthy of consideration here. So as well as reflecting upon the support that community members need, think about your own needs and how to manage these.

In the articles/examples that you found, what learning did you also see reported and what can you take from this? It is wise to be aware that you will need to respond to challenges, so can you factor in some time to support working to resolve any issues that emerge? Challenges can be variable and of course very difficult to anticipate, though it is always worth thinking about conducting a risk assessment at the start of your project, linking this to your analysis phase. You could discuss this with participants and update it as you work through the analysis phases.

Learning Task 4 – Inclusive approaches to participatory analysis

Working inclusively is important in relation to the underpinning principles of CBPR. You can use the basic principles of CBPR as a basis for your plans in relation to analysis.

Are you able to train people appropriately? Training is not the same as delivering module content as a university lecturer, it requires different skills, time, flexibility and the ability to adapt to the needs of each community context and member. Might you need to work with other professionals as well such as staff from non-for-profit organisations, and other stakeholders? Being inclusive is also about listening to professionals, and community members, though these may not always agree with each other. Therefore, you will need to have some ideas about how to achieve compromise, and be prepared for conflicts, emotions and difficult conversations.

You may need funding to support training – travel expenses, venue hire and refreshments are important considerations. Are you anticipating that people will donate their time or are you able to offer them payment? There are many complications associated with both of these options.

Finally, don’t forget to consider how to involve people in terms of the skills that they have (see learning task 2 for more on this).

Chapter 7

Learning task 1 – The ethics of involving participants in dissemination

In completing this learning task you will have had the chance to reflect on a dissemination approach involving young people. By being involved in the dissemination and potentially presenting research findings young people may be challenged to answer questions from adults. What types of training and support would you as a researcher be able to give them to help them with this? In your view, is it ethical for young people to be put in a position where they face challenge when they are volunteering and are less experienced than perhaps paid researchers?

There are many complexities associated with dissemination involving young people, as well as the ethical tensions that require resolution when attempting to implement participatory approaches to dissemination for example, if young people want to use video is this harder to then anonymise participants?

Finally, you should have reflected upon involving young people versus researcher-led approaches to dissemination and the ethics of each of these. It is likely that we may have different opinions about this depending on our own stances because ethical principles can guide us, but they are open to interpretation. However, if you are committed to working in participatory ways, then participant involvement in dissemination is ideal and should be facilitated.

Learning task 2 - Context and participatory dissemination

In completing this learning task you will have realised that context is a significant factor influencing the participatory dissemination of research findings. Much of the literature discussed in chapter 7 illustrates considerations about local issues, differences in needs, understandings and requirements within participatory dissemination. There are useful reflections from researchers about how to explore the needs of different population groups for example, indigenous populations have different dissemination requirements to other groups of people. The examples provided in table 7.3 also highlight that communities (when involved in participatory research) are able to articulate their requirements about products based upon their local insider understandings. See the LSE Blog ‘The “long tail” of research impact is engendered by innovative dissemination tools and meaningful community engagement’ for more on the importance of longer-term dissemination involving community researchers.

Learning Task 3 – Challenges associated with participatory dissemination

When you were compiling your list of challenges to participatory dissemination, were you able to segment them according to different types of issues? The table below illustrates some examples for you to consider as a starting point. Consider how these map to the list that you made.

| Level of challenge | Examples |

| Practical | Time available for all Transport for community members (e.g. to events) Budget issues and the need to offer incentives to encourage involvement in dissemination |

| Power dynamics | Competing agendas Competing requirements/needs associated with the research outputs (papers versus community impact) Style of the project leader and personality |

Learning Task 4 – Doing dissemination

What did you list as being the most useful from the resources that you accessed? Tips vary but here are several reflections that we gathered from our own searching:

- involving all ‘partners’ seems an obvious tip however, in reality some may wish to be less involved, or in fact have less capacity to contribute

- establishing and following procedures for dissemination, including authorship and credit is very useful – to avoid any issues, conflicts and misunderstandings it is helpful to have such policies in place (agreed by all involved ideally) before dissemination begins

- disseminating for policy and/or social change, may well be dependent upon the context of the research and the political environment at the time of the research, but should always be considered. Defining the purpose of dissemination is important in enabling involvement

- did you find information on disseminating “lessons learned” to benefit others working in such ways (for example, new and emerging CBPR partnerships)? This is again more feasible in some instances than others but looking at lessons learned can help in creating checklists to support participatory dissemination.

Chapter 8

Learning Task 1 – The challenge of academic demands

In completing this task, you will have found that there are a huge range of funding opportunities from different sources, see some examples below:

| Funding source | Example | Website |

| Government | The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) which is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. | Website |

| Charities with a specific remit | The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) is an organisation focused on solving poverty in the UK. | Website |

| Charities with a broad remit | The National Lottery Community Fund is a non-departmental public body which distributes money raised from the National Lottery. The money funds evaluation of programmes in addition to the activities related to community groups, health, education and environment. | Website |

| Private organisations | Ferrero has community programmes as part of its corporate social responsibility agenda and in 2015 commissioned Leeds Beckett University to carry out a piece of research on young people and physical activity. | Website |

Websites for formal state funding bodies provide a great deal of detail for funding applicants, and you can find a lot about what outputs they will expect from funded projects.

Specifically, funded researchers are expected to publish the main findings in a peer-reviewed, open access journal. Dissemination through oral presentations, research reports, books/book chapters and press releases is also encouraged.

Community members can be involved in the process of dissemination (see chapter 7) but when researchers are obliged to publish, it must be made clear that there is a limit to community ownership of the data.

There is no definitive answer to how to reach a balance between doing research with people who are struggling to get by versus not including them at all, but researchers should aim to offer a range of ways for community members to be involved to suit their different capacities to contribute.

Learning Task 2 – Inclusion and report writing

Koster et al (2012) discuss collaborative writing and feel that it does not have to involve “the actual drafting, writing, or editing of text” together, nor should it be a case of academics adding authors as a gesture that has no meaning to the community. It is not for the academic to decide the validity of a community member’s contribution and working with a community member to write academic papers or reports is an integral part of the analysis of the project.

There are a variety of ways that academics can include community members in a meaningful way:

- Workshops - The academic partners can provide training to community members on report writing and provide examples of previous work. Workshops can also be used to sense check analysis and academics can present some of the written up work to get input from other stakeholders.

- Language – findings must be accessible to everyone involved. Ideally reports should be produced in plain English or as a minimum, summaries should be available in accessible language and all community languages.

- Visual summaries – findings can be presented using pictures, models, flow charts. There are image banks to make information accessible to people with learning disabilities e.g. http://www.easyonthei-leeds.nhs.uk/

Learning Task 3 – Researcher safety

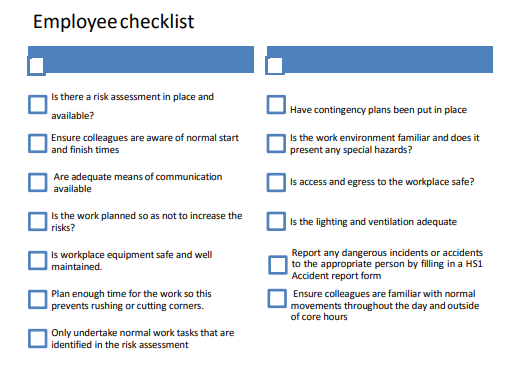

In a risk assessment form, you will be asked to consider:

| Risk | Example |

| Physical | Extreme weather, geographical difficulties |

| Biological | Aggressive animals e.g. loose dogs |

| Chemical | Pesticides |

| Manmade | Vehicles |

| Environmental | Pollution, rubbish |

| Emergency procedures | Fire, first aid |

| Personal safety | Lone working, risk of violence |

The researcher will have to estimate the likelihood of the different risks and the severity of worst-case scenarios. Part of this process also involves considering how to minimise the identified risks and how to deal with them if they arise. Workplaces/universities will have well established risk assessment guidance with specific recommendations for aspects of personal safety, such as lone working. Below is an example of a checklist for lone working from Leeds Beckett University:

Below are some things to think about for a risk assessment for a focus group being held in a community centre at 8pm in winter in a deprived area of the city:

| Risk | Example |

| Physical | How will the researchers get to the community centre? If public transport is not reliable or does not go close to the centre, then a taxi would be preferable. For private cars, think about parking and potential damage to the vehicle. |

| Biological | Aggressive animals e.g. loose dogs |

| Chemical | What other uses is the centre put to? What risks are present in the surrounding community e.g. drugs. |

| Manmade | Is the building itself structurally safe, warm enough and with appropriate facilities. |

| Environmental | Are there risks in the area around the centre? E.g. broken glass, needles. |

| Emergency procedures | What happens in case of fire at the centre? Do the researchers have first aid skills? |

| Personal safety | Number of staff members – it is good practice for any focus group is to have two researchers, especially in this case. Are the participants known to the researchers? Are there risks of violence or aggression from community members? |

Learning Task 4 – Scenarios in the field

There are many ways you could deal with the scenarios presented in learning task 4 and in real life there would be more context to take into account. Here are some suggestions from the authors’ experiences:

- Kim is a strong-willed participant who is dominant in meetings and is adamant that the focus of the research should be an issue which affects her but is not relevant to the rest of the group.

It is helpful to encourage groups to develop their own rules for community meetings so they have ownership and can enforce them e.g. respect other people’s contributions, decide on actions by majority votes, take turns to speak. If these ground rules are firmly established from the beginning, many difficulties can be avoided.

Having an agenda and a chair for meetings can support the group to keep to topics and give everyone the opportunity to speak.

Compromise is an important aspect of the work. If Kim is very passionate about a topic, then she will hopefully be very active in the work. Perhaps her topic could be included in some way in the main research.

- Dennis is a single father with 3 young children and does not have any childcare support but community meetings are in the evening. What are the considerations if he brings the children?

A risk assessment is necessary if children attend the meeting. The group need to decide where the children will be during the meeting and what they will do. If childcare is a challenge for a number of people, the group could look into the possibility of having a creche or playworker present.

It may be possible to hold some meetings at different times or Dennis could phone in to the meeting from home using a video chat app.

- Gerard has an alcohol problem and can be aggressive after drinking, he wants the university researcher to visit his home to discuss some data collection.

This represents a high-risk situation that should be avoided. The researcher can offer a number of alternatives, such as:

- Meeting in a public space – a café, library, on campus. Ideally the researcher should not be alone with this individual even in a public space.

- Discussing the work over the phone/skype

- Meeting as a group earlier in the day

The researcher should discuss this with colleagues and trusted leaders in the community to protect everyone involved. If the individual becomes threatening, the researcher should always be in a position to call security or the police. It is necessary to have a charged phone with them at all times.

Chapter 9

Learning Task 1 – Key components of Community Campus Partnerships

In completing this learning task, you may have found a number of examples of CCPs in the United States. There are also several examples in the UK. The University of Brighton’s Community University Partnership Programme (CUPP) is one example of an established CCP. It began in 2003, initially with external funding from Atlantic Philanthropies and subsequently received core funding from the university and support from senior members of staff (Hart et al, 2007). The CUPP website gives details of previous projects including a map showing the locations where they took place:

At Leeds Beckett University, an initiative called CommUNIty (putting ‘uni’ into the community) was set up in the Faculty of Health and Social Sciences with a view to building strong community partnerships to facilitate knowledge exchange and mutual benefit through staff and student research (though this is not always participatory), placements and volunteering. Although a great deal of work always takes places between the university and community partners, particularly in the fields of health, education and research, it is often quite disjointed, and colleagues are not aware of what is happening in the school, faculty or wider university. By forming a CCP, the role of a key contact or “critical bridge person” is created which can allow partnerships to be more coordinated (Ostrander, 2004).

One significant issue for individuals or groups outside of the university is how to access the resources within; there is no physical or virtual front door that they can knock on or a direct line to a person who can help. CUPP established a helpdesk to act as a point of contact where enquiries could be directed about research or knowledge exchange and then connected to the appropriate academic (Hart et al, 2007). It also delivers seminars and workshops on research skills and facilitates drop in events and a community research forum (Ibid.). CommUNIty at Leeds Beckett welcomes contact from community members and can be reached through email or Twitter.

Learning Task 2 – Civic Universities, do institutions have an obligation to the citizens of their city, beyond the students?

In 2019, the UPP foundation (an independent charity) produced a report called Truly Civic: Strengthening the Connection Between Universities and their Places. The report highlights the challenge of universities becoming more nationally or internationally focused at the expense of their own region: “as universities have become magnets for global students and massive research programmes, their connection to their place and the people who created them can sometimes be called into question: how are the people in a place benefiting from the university success story?”

Higher education is one of the largest employers in the country, universities bring thousands of students into their towns/cities and as a result have a significant impact on the economic and social wellbeing of their surrounding community.

The report outlines a number of recommendations about how universities can support their local communities to face existing challenges and also help them to adapt to new ones such as the ageing population and the effects of increased automation on jobs. These recommendations include: increasing funding to support civic university activity; sharing good practice; widening participation especially adult education; and prioritising local impact as well as national/international.

A summary of key benefits of CCPs for universities and community groups was included in chapter 9:

| For the University | For the Community |

| Widening participation: a diverse student body to reflect the community the university serves | Access to education and training, raising aspirations |

| Enhancing student experience | Informing student learning to serve different communities better |

| Access to community knowledge | Access to academic knowledge |

| Research opportunities | Research opportunities – co-producing research agendas |

| Ethical access to research participants | Informing research priorities |

| Research impact | Evidence led service development |

| Volunteering and placement opportunities | Increased capacity through access to staff/student support |

| Meeting Corporate Social Responsibilities | Working towards shared goals, greater sustainability |

| Addressing the power imbalance, a less exploitative model of working | Increase control and power in the hands of the community |

Learning Task 3 – Brokering relationships

In this learning task you will have had a huge variety of charities to choose from. Let’s take the example of the homeless charity discussed in the case study in this chapter: St George’s Crypt. You can find a list of the charity’s priorities under their mission statement where they cite their aims. Below are some examples:

“We Aim:

- To help people gain skills and confidence so that they can take an active role in their futures.

- To enable people to make positive choices in their lifestyle by accessing employment and freedom from addiction.

- To find the most appropriate solutions by creating effective partnerships across the city.”

You can then look at the websites for the universities in the city e.g. Leeds Beckett University to see what areas of teaching and research could support the aims of the charity. In the School of Health and Community Studies, you can see there are courses in Psychological Therapies & Mental Health; Nursing; Health Promotion; and Social Work that would complement their priority areas. The School of Clinical and Applied Sciences could offer expertise in Physiotherapy, Occupation Therapy and Nutrition.

As the charity specifically mention addiction as an area they want to address, a project could be created using the expertise from Psychological Therapies & Mental Health, Nursing and Occupation Health to work with clients to deal with the physical, mental and daily challenges they need to overcome.

Learning Task 4 – What are the potential challenges of this work?

A number of challenges were discussed in the chapter, did you identify others that you have encountered? The main ones we covered were:

- A lack of clarity of boundaries

- Achieving a balance of power

- Historical issues between individuals causing difficulties

- Conflicting priorities of communities and the university

- Different cultures of working and ways of speaking

- Time to build relationships and complete research

- Funding and sustainability

- Representation and diversity

For most of the potential challenges, clear and ongoing communication were found to be the best ways of avoiding or minimising difficulties. Having designated people to coordinate work through the CCP helps to promote good communication and to bridge the gap between the university and the outside world.

Chapter 10

Learning Task 1 – Exploring definitions of impact

In completing the learning task you will have seen that impact is defined and discussed in a broad variety of ways, and some of the definitions and examples will align more to participatory principles and approaches, than others. If impact is for example defined as a high impact research paper being published, then this may be inaccessible to many community members. Involving them in the production of writing for publication may also be well-intentioned but not necessarily align to their views of impact. So perhaps academic impact and economic impact are less aligned to participatory research when compared to the points made on the web-pages about capacity building and instrumental impact (specifically service development, change and/or improvement).

Did you also find some advice that is useful in terms of your own participatory practice? Given the varying definitions of impact, you can think about which definition is most suitable to each project, and how this fits with your own approach, as well as the wishes of community members/lay researchers. The final point made on the page we are discussing, mentions the importance of supportive environments, practice and many years of research activity – how do your own circumstances enable you to understand, develop and achieve impact within your own participatory practice?

Learning Task 2 – Mapping Alternative Impact

There are fourteen headings in this report that discuss impact, so lots to consider here. The report makes the suggestion that bigger is not always better, and that it is important to consider impact from process as well – see boxes 10.1 and 10.2 in the book itself for specific examples of process-related impacts. The paper also talks about impact as being mutually beneficial, and so in each participatory project you can consider your own learning and skills development as well as that of community members. In addition, what is the added value in terms of impact from such approaches – might this be relationship development, increased understanding of issues, a different research approach, a new ‘impact’ that you had not considered creating before. Do these comments resonate with your own reflections?

The report is an accessible and useful document in terms of expanding upon the more traditional academic approaches to impact that have been discussed in the literature. Several of the recommendations (did you read these too?) are directed towards research funding agencies. However, recommendation 3 that discusses demonstrating impact suggests that a wider range of methods and measures for demonstrating impact should be used, therefore consider how your own approach can map impact perhaps using some of the alternative approaches suggested such as holistic evaluation, participatory evaluation and values-based evaluation. Mapping the impacts from your own participatory research should ideally be part of your considerations.

Learning Task 3 – Challenges associated with impact

In completing this learning task, which challenges did you feel were the most worrying for you and your participatory research project? All research (including traditional approaches) is compromised by the time available, and funding limitations so participatory approaches of course raise the same challenges, as well as additional considerations. Each context in which the research is taking place is also likely to raise different challenges – a deprived area compared to an areas with many more assets raises questions about involvement, skills, and links to those in power to effect change. How are your own skills in terms of research and relationship building – do you have the time to commit and realistic expectations about the process, as well as the impact. For example, you may not always be able to achieve the publication of a paper from participatory research projects.

What is it that community members want to see too, and can this realistically be achieved? Do they expect immediate service change or the creation of a new service? Do they expect you to work more quickly than you are able to? How can you manage expectations whilst maintaining trust and achieving compromise in relation to impact?

Learning Task 4 – Translating research into impact inclusively

This learning task encourages you to think about working with community members in order to view impact through their eyes. Impact in such instances can be linked to dissemination (see chapter 7 for more on this) – is impact about disseminating research findings into local organisations and community groups and making some small changes? Can you work with community members to include their ideas, and then to implement some (if not all)? If your project has specific funding for dissemination, you can include community members in deciding how to spend this budget e.g. on the creation of an event, a product, on training etc. What will happen when funding runs out – are you able to still offer some support to community members who wish to continue to work to build impact? If you are able to maintain links to those who were involved, then might this enable you to continue to map impact (see learning task 3), and to see the ripples that are developing over time (assuming that these are produced).